this piece is part of OPTIMISED LOVE, our first digital collection of works.

Calabash Dolls

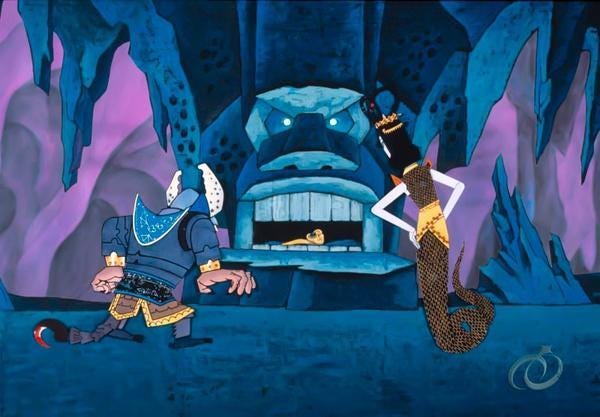

Calabash Brothers was a Shanghainese animation series from the 80s about an old man who grows seven bottle gourds in seven different colours to rid the world of two evil spirits. The seven gourds dropped sequentially to the ground, each turning into a young boy with a different superpower.

I used to watch a bootleg version on my grandparents’ flickery CRT whenever I visited. I had a crush on each of the brothers, my favourite being whoever was on screen at the time. The official title of the show was 葫芦兄弟 (Húlu Xiōngdì), which translates to “Calabash Brothers”, but they were colloquially known as 葫芦娃 (Húlu Wá), where “Wá” is an endearing term for small children or a doll. Liking boys is uncouth, but liking, even loving dolls, is totally okay and normal.

The dolls had to save the world from the Serpent Queen, a majestic and startlingly beautiful evil spirit who was half woman and half snake. She awoke from a cursed slumber after being confined underneath a mountain. I was scared of her, but she was mesmerising. Her partner in life and evil was the Scorpion King, who had no relations to the character played by Dwayne Johnson in the 2002 film of the same name, but was similarly ugly and uncute in the way that pre-teen me thought all things manly were ugly and uncute.

I didn't have a lot of IRL dolls because they were expensive and frivolous, and my immigrant parents would have rather spent that money on books (they didn't actually buy many books though since the library was free). The Calabash Dolls were good enough, especially when I took the burned DVD home with me one visit.

Cruel optimism X tertiary protention

Does time go by faster as you age? “Apparently, it's because we don't renew our synapses after 20,” says Céline, as she sits across from Jesse in a Parisian café in Before Sunset, seeing him for the first time in 9 years. Or does time go by faster because of our technologically accelerated reality such that it’s not our age but social acceleration? For my grandparents in their prime vs me in mine, what is the length of an hour?

If time is only ever phenomenological, then it's the technology-induced brainrot that has altered time, its cadence and flow. This is tertiary retention, a term used by philosopher Bernard Stiegler to describe artificial memory, memory external to human psyche. It’s also tertiary protentions, similar to its retentional counterpart but for anticipations instead of memory. The exteriorised memory of the internet as archive, blockchain as contrived synchronicity, and artificial intelligence recursively modifying processes and behaviours are all symptomatic of a technological, tertiary reality set between these tertiery retentions and protentions.

Technology is thus integral to experiencing futurity, when our protentions are contingent so heavily on the technics that construct our past and present. Yuk Hui, who coined tertiary protention, designate protention as “...imagination, through which we recollect and recognize what we have experienced and project it into the future.” Imagination thus becomes subject to technological progress and output.

There’s something bleak about futurity contained within technological capacity (which inherently answers to the dictates of the market) that reminds me of Lauren Berlant’s cruel optimism. All attachment is optimistic, but it becomes cruel when your attachment to something desirable becomes an obstacle to your flourishing. It restructures the phenomenological time of imagination such that the contours of affective life fold into itself to form an ouroboros of desire/deterrent. Cruel optimism is the future-facing hope and anticipation that comes into disrepair due to the very mechanism by which this potential future is first gazed upon.

Cruel optimisation for the lovelorn

All affect is mediated through the technological, if not in the first instance then in a pre-loved way, where meaning is built on mediated meaning somewhere along the line. This is especially true in the digital milieu, where algorithmic governmentality infiltrates every crevice of our existence, psychic and physical, economic and emotional. It leads to what Antoinette Rouvroy has called an optimisation society, where optimisation effectively kills imagination.

Our collective protentions are thus subject to unbridled collapse, and our attachments are inherently cruel. No longer simply cruel optimism, we face cruel optimisation whereby our affective lives are rendered through tertiary protentions and retentions that abide by the directional logic of algorithmic governmentality and rampant optimisation.

Optimisation on an algorithmic level is the constant, metabolic pulse that drives a linear path towards an unknowable goal, yet always a goal that aligns with profit maximisation. What does this mean for love? It’s no secret that algorithmic dating leads to addiction rather than any fulfilling relation, even if the lawsuit addressing this last year wasn’t won on behalf of the lovelorn. It’s cruel and it tracks, but there’s more to it than an endless cycle of swipes and subscription renewals. The constant, insatiable hope for fulfilment and companionship is only one of the outcomes of cruel optimisation. The other, which makes itself known if ever you manage to find sustained romantic love, is progeny.

The childless, they say, are ungovernable, unforgivable, unoptimised and unaligned with economic growth. Yet to give in to fecundity is to give in to another cycle of cruelty, a love so intense yet so cursed as to sacrifice it to the needs of labour.

The Serpent Queen, childless but with the embrace of romantic love, cannot be computed in the natural order of things and becomes a virus to the land. What better way to rid of her than with 7 magical boys and an old grandfather figure, the harbingers of patriarchy and traditional family values? In the age of optimisation, love without an end-game purpose or a palpable bottom line will be extinguished. Ever-breedable, ever-submissive, optimised to never be fulfilled (except maybe with semen, seeds?) is the only way.

Irony or ecstasy?

So, what to do? If our affective lives and deepest desires, be it love or lust or lurid commodities that satisfy our appetite to consume the newest trend cycles, are doomed to stand in the way of the good life, how do we detach and forge another way, a new horizon of imagination?

I once thought the solution had to be something related to the nihilism of internet culture. Both optimisation and optimism relates to a certain form of sincerity, a grotesque and cloyingly saccharine type of earnestness such that only a post-ironic form of meaning-production could undercut this sweetness, these logics. I'm not so convinced anymore.

In adulthood, of course I desire and aspire to be the Serpent Queen more than I ever did the dolls. Her love is unadulterated, without objective, the antithesis of the 7 children who bring prosperity and growth, wholesome in their pure goodness that uplifts and protects the old man who grew them from gourds as progeny, as if from immaculate conception. She is loved in spite of her evil intent, loved just because she’s hot. I want that, not to just desire but to be desired, the object of someone else’s affective life which controls their attachment and futurity. I think it’s not irony, actual or post, that emancipates us from cruel and constant optimisation, but ecstasy, which might be likened to escape, release for only the pleasure of the present and without regard for an aim beyond such a moment. If optimisation is an ever-moving goal post recognisable by its forward-oriented directionality, ecstasy provides a tangible bookend. Even if the love is redirected from something ugly and uncute and manly, it’s how you get a moment of post-nut clarity, such that a new horizon for imagination might be rendered, one which puts into perspective the scam of algorithmic attachments and the optimisation culture which makes love impossibly cruel.

𝓼𝓪𝓷𝓭𝔂 𝓭𝓲 𝔂𝓾

Sandy Di Yu (she/her) is a PhD researcher in Digital Media at the University of Sussex and co-managing editor of the CHASE DTP-funded DiSCo (Digital Studies Collective) Journal, with an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research focuses on the aesthetics of optimisation. Sandy has written extensively on visual culture, working with several arts organisations and publications from the UK and beyond.