Princess Lumpy Nayland Space Blake Princess: A Close Reading of a Cosplay Portrait and Its Citations

by Matt Morris

⋅˚₊‧ 𐙚 ‧₊˚ ⋅🏰 this piece is part of PRINCESS, our second digital collection of works. PRINCESS responds to the problematic of modern princessdom through pieces by theorists, writers, and artists. 🏰⋅˚₊‧ 𐙚 ‧₊˚ ⋅

。 ₊°༺❤︎༻°₊ 。

I have been rummaging through the glut of princess rhetoric that permeates present popular culture, sidestepping the generally paternalistic, un-feminist bits in search of iconography (ontologies?) of some efficacy—not positioning ‘princess’ as useful, per se, but as pluralistic and possible. I was of a queer age group that came into formation on Tumblr. Many of my friends, lovers, companions, and collaborators were discovered through our shuffling and sharing of cultural fragments. In that time, I was also tracing my artistic lineages and embracing my place among fandoms—comics, film, fashion, drag, pop culture.

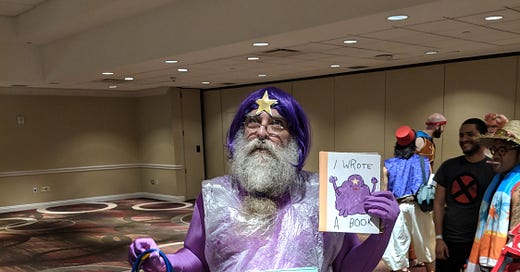

As I began to gather my thoughts around ‘princess’ as positionality, there was a memory that I worked back toward. It was an image taken of an artist who has been deeply influential to me, and I believed I remembered that in it, they were a princess. I wrote to them, and they graciously shared a copy of the picture (Figure 1). I pressed play on Shania Twain’s 2002 bop “I’m Gonna Getcha Good,” on repeat, and attempted to write my way into an understanding of what this image is doing.

A beatific angel of shimmering violet, a queer non-binary approaching-elder, bearded in silvery filaments, septum pierced, bespectacled, a gold star like that which would adorn a perfect grade on a homework assignment placed at their third eye, sporting deeper purple sneakers and pinching the straps of a vintage blue purse. Their grape flavored wig is the sister-counterpart to Natalie Portman’s shake-and-go bubblegum bob in Mike Nichols’ Closer, 2004. Draped over a catsuit of violet-mauve lycra (that might have been smuggled from an early episode of the original Star Trek series) is a shift dress made from translucent plastic bag: the compounded sheen of the materials dazzles, recalling the clear cellophane sheaths which painter bon vivant Florine Stettheimer used to decorate her salon as abstract bouquets spilling from vases, festooned curtains, and futuristic tumbleweeds haralding modernity’s rise. Accounting for the high camp, this princess poses like Edith Wharton’s enviable, celestial Daunt Diana; in the combination of dainty mannerism and cosmic cosmetic flash, their visage evokes Baudelaire’s uneven not-always complimentary address of the feminine as “a divinity, a star, which presides at all the conceptions of the brain of man; a glittering conglomeration of all the graces of Nature [sic], condensed into a single being; the object of the keenest admiration and curiosity that the picture of life can offer its contemplator. She is a kind of idol, stupid perhaps, but dazzling and bewitching, who holds wills and destinies suspended on her glance.” (Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life). The poet meant nothing nice in calling women stupid, but this image holds that marker too, regalia conjunct fancy dress, royalty conjunct court jester.

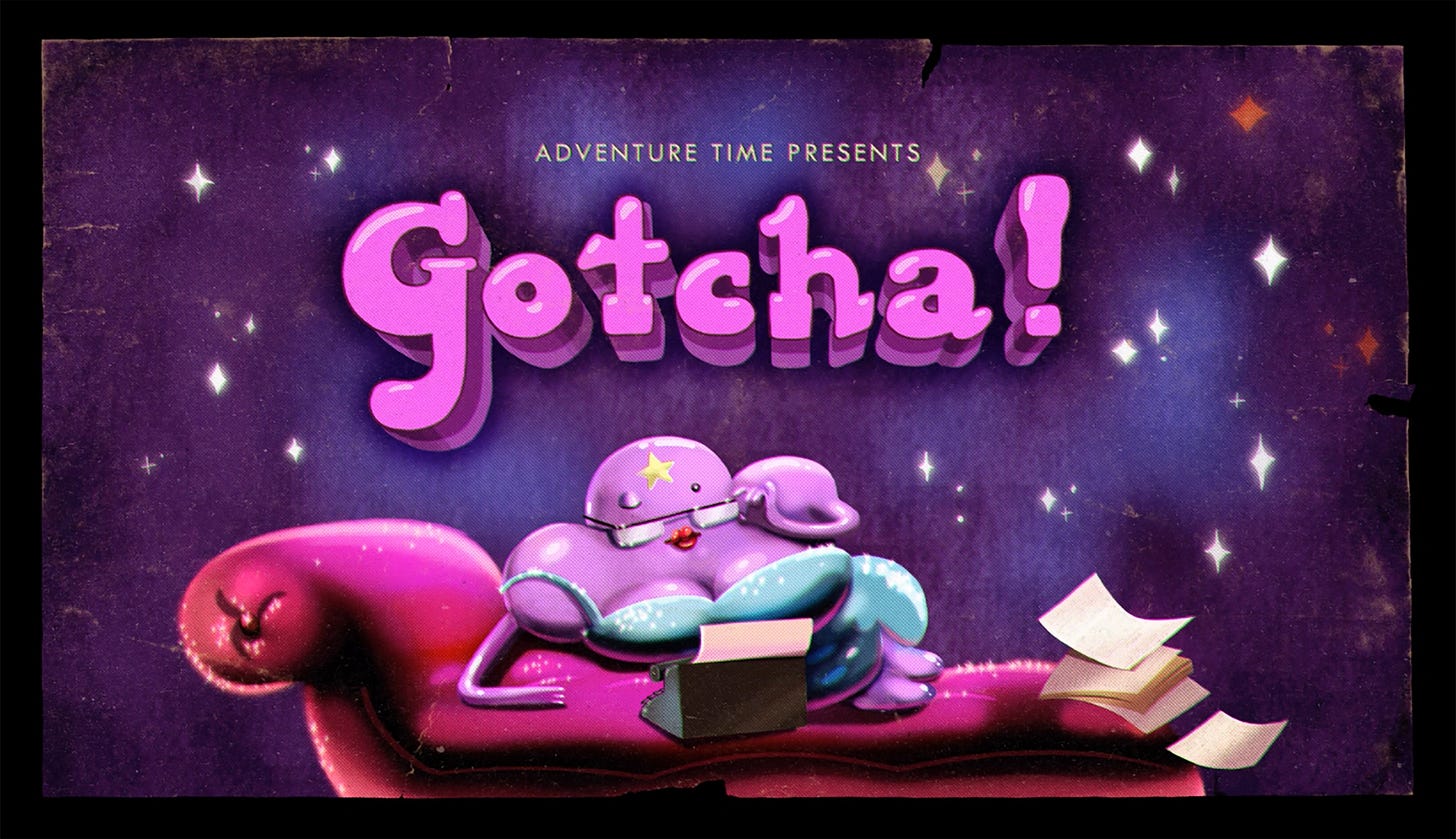

Standing contrapposto in some corridor of a hotel or conference center (or both), atop emphatically Stylish carpeting in an otherwise beige and khaki purgatory of hyder-adaptability, Nayland Blake—a fairy godparent among contemporary art scenes, kink scenes, queer subcultures, fandom cultures, and any place where multiple valences intersect—is attired as Lumpy Space Princess (or LSP as she is often referred), a character from Pendleton Ward’s Adventure Time, a serialized animated fantasy that ran on Cartoon Network from 2010 to 2018. Lumpy Space Princess is designed as a levitating lilac cloud with eyes, mouth, and arms—a parameter of convex scallops (lumps) arranged around capricious facial expressions that skew impish at every occasion that would call for imperial. Within the ongoing plot of Adventure Time, Lumpy Space Princess has defected from her extra-dimensional kingdom and for most of the series lives relatively unsheltered in the forest. LSP flouts tradition probably more than she realizes, her personality an erratic combination of confidence and anxiety, entitlement and delusion. A gender flipped and consolidated prince-as-well-as-pauper, LSP consistently tests limits, assumptions, and societal defaults as a proverbial Lump Who Fell to Earth.

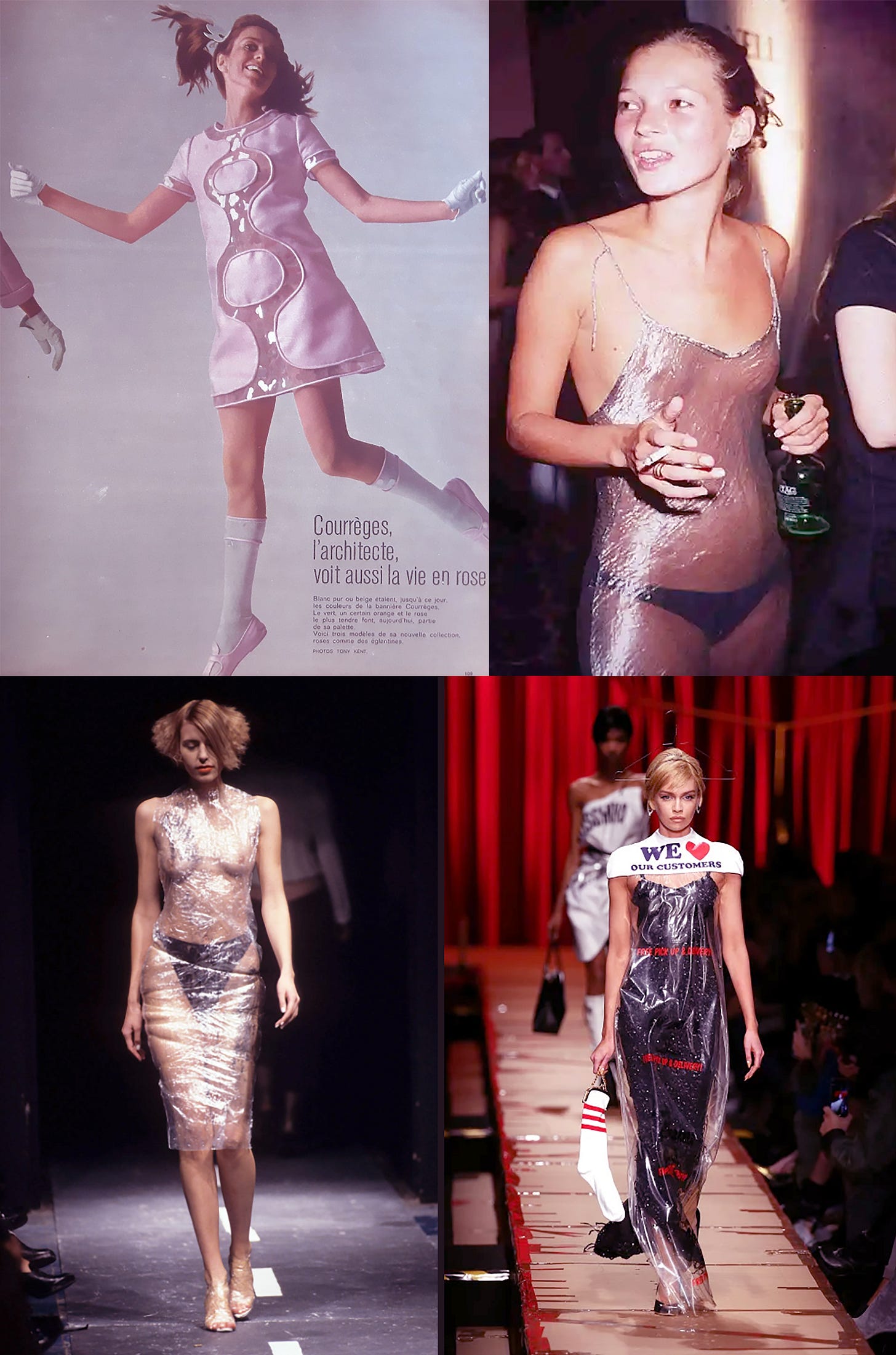

Specifically, this photograph shows Nayland Blake costumed as a character who is in costume, making reference to the episode Gotcha!, Season 4, Episode 12, in which Lumpy Space Princess goes undercover as an ‘adventure secretary’ in order to gather material for a book on the art of romantic attraction she is determined to write. “I always wanted to write trashy books for ladies!” exclaims LSP. Adopting a persona equal parts Nellie Bly-style investigative undercover journalism and Jackie Collins-style pandering eroticist, Lumpy Space Princess attempts to exercise her attractive wiles in a disguise comprising mostly a plastic SQUEEZ-E-MART shopping bag—a style move redolent of ‘Space Age’ plastic attire by Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges, and Paco Rabanne in the 1960s; subsequently updated in key moments such as the sheer Liza Bruce slip dress Kate Moss was photographed wearing in London in 1993; Alexander McQueen’s 1995 ready-to-wear collection of cling wrap, bin liners, and other elevated plastic banalities; and Jeremy Scott’s ‘cape sheer overlay dress’ made from a plastic dry cleaning bag, ‘designed’ for Moschino in 2017 (Figure 2). At the close of the Gotcha! episode, Jake the Dog yells in frustration, “LSP, you’re wearing garbage for clothes!” This is one of a panoply of interventions and interjections throughout the series that underscores Lumpy Space Princess’ strategic subversions, unwitting inversions, and ‘disidentifications’ with the rote categories she navigates.

I can’t speculate on the significance of Blake’s decisions around dressing as this character or the citations of this specific episode; rather, as has been part of my own psychoanalysis ongoing, I want to read the image, its confluence of citations, and its effects, particularly in the context of theorizing ‘princess’ as a position. Costume isn’t unrelated to Blake’s multimedia art practice. Fantasy, roleplay, dress up, make believe, and transformation are consistent tactics within a field of playful inquiry in the artist’s work since the 1980s. Queerness, fatness, biracial heritage, and questions of ‘passing’ are just some of the identity categories that Blake has insisted on interrogating as lived experiences rather than labels and taxonomies. In their installation Equipment for a Shameful Epic, 1993, a rack of costumes and props allude to violent histories, imperialism, and upset power relations with gold crowns, a scythe, a noose, a judge’s wig of white ringlets, wands, a fake severed leg, masks painted with artificial blood, a wooly grey beard, furry suits, superhero uniforms, and an assortment of other gear. In the 2000 video performance Starting Over, the artist is seen tap dancing while wearing an enormous white rabbit suit with stylistic inflections of Maurice Sendak’s endearing monstrosities—the garment’s materials are listed as cloth and 140 pounds of beans. In 2017 Blake presented what they called their ‘official fursona,’ a furry avatar named Gnomen, at the New Museum as part of the expansive exhibition Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon. A chance conversation with

Jamillah James, who curated No Wrong Holes, the thirty-year survey of Blake’s work for the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, in 2019, brought my attention to an earlier alter ego in Blake’s oeuvre, Princess Coco, who has existed in the artist’s life and work in print, performance, and other experimental permutations—an precedent for their Lumpy Space Princess. These are just a few scant examples from a plethora of permuting characters and costumes from the Blake oeuvre. Relevant to the LSP-in-trash-bags references, in 2013 Blake shared a story on the podcast RISK! about donning a sanitation worker’s uniform to attend the Black Party, the annual vernal equinox bacchanalia in New York City’s gay nightlife and leather scene. Such community and collaborative expressions of creative eroticism, shared world-building, and fantasy-made-real have been touchstones in the cultural contexts for Blake’s work.

This photograph was taken of Blake in 2018 at Flame Con, a comics and pop culture convention oriented toward LGBTQ+ creators, fans, and properties that has taken place in New York since 2015. At the end of 2018, Blake told Artforum, “Flame Con has become my favorite annual queer pride event, mostly because of the way it allows artists and fans to create and enact new types of queer identities and stories through dressing up, performing, and celebrating one another’s work. While the rest of the cultural landscape struggles with minimal amounts of representation and massive conservative backlash, Flame Con proves that there is a flourishing, diverse, loving community emerging from the grass roots of American culture.”

A native New Yorker, Blake’s art education took them to Bard College and CalArts before their move to San Francisco in 1984, a queer time and place that proceeded from the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot of 1966 and the irreverently gender non-conforming ‘skag drag’ of the Cockettes and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. There’s a claim to be made here that cosplay, furry subcultures, and other various politics of ‘dressing up’ have been indelibly shaped by those San Franciscan and similar experimental approaches to drag as art, performance, and life. Five years before the launch of Flame Con, RuPaul’s Drag Race premiered as a televised showcase of drag artistry; despite its relative conservatism in how it has represented drag to wider audiences, it has nonetheless provided some context for a practice defiant of gender, class, and circumstances—using ‘dress up’ as a strategy for fugitivity that fashions ‘queen’ from artifice rather than any kind of tradition of ‘divine right.’

Lumpy Space Princess, particularly as she is performed by Nayland Blake as a kind of cosplay drag, is generative in her morphology, her mobility, and her rebellion as a set of strategies toward constituting princess as a radically unstable sign. Approaching Nayland-as-drag-LSP, the distinct departures from princesses of classic fairytale and myth evidence themselves: that is, this cartoon alien princess translated into makeshift costume design in the spirit of Oskar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus costume parties of the 1920s stands (in leggings and athletic sneakers) at odds with one of the central tenets of the cultural convention of ‘princess’—that the position is marked by a need of rescuing. ‘Princess’ is a site at which liberation is anticipated. In lore, the princess is liberated in such a way that consolidates power, agency, and authority continually onto patriarchy and its princes at the expense of witches, sea-witches, sorceresses, so-called

evil queens, and a gamut of femme figures toppled from whatever transgressive power they asserted with vanity and hubris. 90s Disney princess stories tempered Prince Charming/white-night-in-shining-armor MacGuffins with some measure of politically moderate Third Wave self-liberation portrayals, but pop culture’s princess imaginary entered the twenty-first century with persistent signals of affluence and oftentimes even enchantment at the uneasy intersection between gender, class, and nationalism.

Still, it’s not as if the tropes of rebel princess or undercover princess or escaped princess are entirely unexplored. Some iconic rebellious princess interlocutors that offer conceptual material toward Lumpy Space Princess: Princess Margaret Rose of York, younger sister of British monarch Elizabeth II, fashion plate, divorcee, frequent subject of scandal; nineteenth-century Persian Princess Zahra Khanum ‘Taj al-Saltaneh,’ feminist activist and founding member of the Women’s Freedom Association; Rebel Alliance Princes Leia; Peach, Daisy, and the coterie of other princess characters in Nintendo’s Mario franchise—especially after they acquire the prosthetics of vehicles in the Mario Kart series; Audrey Hepburn’s absconded-in-Rome Crown Princess Ann in the 1953 rom com Roman Holiday; et al. These and plenty of others provide some precedent to the ways that Lumpy Space Princess (and also Nayland Blake and most of all Nayland Blake as Lumpy Space Princess) approaches forms of refusal, transgression, and revolt.

The irony of the princess is that her so-called liberation is traditionally a re-assimilation into the systems of control and order over which kings and sky-gods govern. Within monarchy, princess indicates liminalities or marginalities in proximity to absolute power, a Goldilocking of neither too little or too much at every threshold. Her ascension into power would typically make her no longer a princess; ‘princess’ is always attendant to higher authority. Impatience is counter to virtue, and desire requires constriction. The question of the actual mechanics of a rebel princess necessitates ambivalence, contradiction, and complexity as tools with which to bolster the possibility of liberation beyond the scope of empire.

Broadly, experimental drag integrates critical dimensions of ideology, indoctrination, fashion, popular culture, and a capacity for roleplay into productive performativity that is not limited to the ‘dress up’ ‘as’ ‘a princess’ in which children, femmes, and those otherwise aspirational might fabulate, but that the accessorization and makeup/making up of a princess is a constitutive feature of its position outright. Modes of frippery, ornamentation, fashioning, and passementerie have served as the devices by which jouissance is expressed but also controlled. While excess vis-a-vis princess is regulated, sublimated, or else rendered superfluous, Lumpy Space Princess—not to mention her place in the chain of significations represented in this photograph—lives a kind of unmanageability. Defection from her own kingdom’s dimension, living outside, and performing lumpiness serve as context for her making up/making believe in Gotcha! with garments fashioned from disposable materials and the particularly polymorphous orality in the sequence when she plumps her lips with the glistening red filling from a ‘Jam Ham hand pie.’

For most any princess, hysteria and frivolity are equivalent—but while this condition is a latent effect or subtext for documented histories of royals, LSP somersaults through a sort of pleasure and actualization around her neuroses, integrating defiance and dress up into the expression of her status as a princess per se. These are radical propositions for maneuverability if not agency outright within hegemonic power: in LSP’s changeling, biomorphic mutabilities—lumps coming and going, extending and shifting (and performing variously ‘as breast’ and ‘as phallus’ and etc. in ways that are unfixed bordering on abject), her simultaneity as ‘more than’ and also ‘expelled’ models dissolve strict divisions between self and other. This occurs too in Nayland’s drag of LSP, and the drag itself also in a kind of disguise as ‘adventure secretary.’ The performance of princess here is multiple and hybrid, ‘free’ in the sense of exceeding restrictions, even licentious, or dangerous as approaching mutation, like free radicals and feeling the ‘lumps’ of cancer cells departing from their surrounding norms.

But as we are aptly reminded by Angela Davis, freedom is a constant struggle. After power resided in the ideology of a divinely appointed authority, it was redistributed across commerce and capital, as well as conceptions of post-Enlightenment interpellated subjectivity wherein selfhood is regulated by the state, identity is always projected onto the individual, and self determination per se is legitimized through a kind of pornographic theater, reification resulting from being witnessed by dominating societal forces. The constant struggle is partly sited at the disjuncture between the transgressiveness by which freedom is achieved and an ongoing negotiation of the publicness that is produced in those efforts. This has been an ambivalent politics in successive liberation movements, among them: the pursuit for women to participate in public life and the complex objectifications that characterize women’s movement in and through the misogyny and heterosexism that governs those spaces; the discomfiting device of ‘representation’ in the project of racial parity, the gaze as a latent means of possession following on centuries of chattel slavery and subordination; the pressure to explicate queerness, the demand for nonnormative sexuality to be demonstrated (for the consumption of het centralisms) in order to be recognized. The ongoing fraught practice of freedom then is inclusive not only of release from subjection but also of reckoning with Foucault’s claim that there is no outside of power and testing when and where refusal more effectively manages the capacities to ‘be’ ‘free’ than active participation. The quandary is that refusal-as-freedom reproduces the appearance if not also the conditions of exclusion/marginalization that necessitated liberation to begin with.

The imaged Lumpy Nayland Space Blake Princess proposes some forms that move into the complex relations of visibility and escape, compliance and refusal, fantasy and law.

● When artist and scholar Lise Haller Baggesen was investigating capacities for the maternal within artistic praxis and disco as an expression of revolution, she noted that despite the strictures of state apparatus and the aesthetics thereof, mixing red, white, and blue results in lavender. To this, we can attach the ways that this in-between hue has signaled queerness variously: Sappho’s violet posies, Stettheimer’s Revolt of the Violet, Lavender Scare, Lavender Menace…. In the opening of her book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, Alice Walker wrote, “Womanist is to feminist as purple to lavender.”

● In degrees of contrast to many of the other central characters of Adventure Time whose designs feature pronounced elongation or willowy pixie statures, LSP is voluminous—a literal modeling of Fergie’s ‘my humps / my lovely lady lumps / check it out.’ Against wellness capitalism and medicojuridical exactitudes, this is a performance of fatness as willfully taking up space and partaking in pleasure. Fat crosses over a boundary as a sorting principle between queer politics and homonormativities. Divested from the violence of beauty standards, norms, and a transposition of het conceptions of desirability, fat is held in dyke marches, disability activism, drag stages, and holistic systems of care in queer community.

● In the arithmetic of beard + purse + plastic bag + dress + etc, this ‘princess’ belongs to a boundless ungendering or more-than gendering. I think of the inclusivity of Shania Twain’s invitation ‘Let’s go, girls!’ Or Monique Wittig positioning ‘lesbian’ as outside of ‘man’ and ‘woman’: ‘Lesbian is the only concept I know of which is beyond the categories of sex (woman and man), because the designated subject (lesbian) is not a woman, either economically, or politically, or ideologically. For what makes a woman is a specific social relation to a man…a relation which lesbians escape by refusing to become or to stay heterosexual.’ (‘One Is Not Born a Woman’) And also the way Griselda Pollock contends with the distinctions to be made between ‘woman’ and ‘feminine,’ particularly in the emergence of modernity, ‘Indeed woman is just a sign, a fiction, a confection of meanings and fantasies. Femininity is not the natural condition of female persons. It is a historically variable ideological construction of meanings for a sign W*O*M*A*N which is produced by and for another social group which derives its identity and imagined superiority by manufacturing the spectre of this fantastic Other.’ (‘Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity’) In the checkered matrices that extend beyond binaries and normativities, we could no doubt proliferate many other concepts to add to Wittig’s lesbian that is not and refuses—for now, I’ll add drag space princess.

● Blake’s pose for this photograph includes a prop based on the Gotcha! storyline. LSP’s investigative journalism inspires her to draft a manuscript that her friend Turtle Princess binds and publishes under the title ‘I WROTE A BOOK.’ So many things happen just in this one component of the scene on view. The text surrounds a simplified drawing of the Lumpy Space Princess character; in presenting it alongside Blake’s cosplay drag, the fantasy is corroborated: they are the lilac cloud creature depicted on their book by virtue of the ‘I’ at play on its cover. The literacy proposed in ‘wrote’ and the imagined reading of ‘a book’ stands now as it did in 2018 as an affront to the debate, disappearances, and erasure of a grammared language that queers gender, personhood, and identity as a sociopolitical practice. In my wishful thinking, every word, term, phrase, and name stricken from federal usage by fascist regimes are teleported into this ‘I WROTE A BOOK’ book. Its past tense account projects Blake’s drag experiment backward into prior existence. The fact of it having been, and further having acted with and within language affirms that queer and non-binary pleasures, desires, and orientations were here already, before now. We come from someone/s and somewheres, and from those vantages we have written, acted, made up, dressed up, and ‘princessed’ about in ways both playful and critical.

This image is an oracle’s promise, a utopian mirage—lavender mist arranged into rococo cumulus embodiment. It is aflame with longing, and also ‘flaming’ in attendance at Flame Con, but also within passively postmodern interior architecture that accommodates these ‘flaming’ fandoms that weekend, while also possibly adapting to opposing or dissenting cultural views in the moments that precede and follow. Class and privilege are upcycled into sartorial plastic specters—the crisis of self determination, the question of agency, the possibility of transformation. This is a performed creature of letters, culminating in a linguistics of their own, ‘reading,’ as in drag ballroom culture, but also a kind of reading that is endemic to camp as a reflex.

At the start of 2020, weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States and sent public life into shutdown, Nayland Blake and I began co-teaching a studio-seminar course at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that looked at psychogeography and the Situationist International as precursors for a discourse on the politics of space and object-making. I began the class by sharing some of the slogans Situationists brought to the May 1968 protests in Paris, among them an adaptation from Herodotus’ Histories: ‘I desire neither to rule nor to be ruled.’ This sentiment more than any other has directed my ruminations on what a princess is, can be, does, could do in this time and place. ‘Princess’ is proximal to rule, but rarely if ever herself rules. If I scour for a rebellious princess that is fugitive to the project of rule categorically, what I apprehend is this moment depicted in layers of information and embodiment, drag becoming princess, art as erotic possibility, defiant of the stranglehold of identities, violet excess with the potential of expanding endlessly.

。 ₊°༺❤︎༻°₊ 。

Matt Morris is a dedicated polymath who has widely exhibited art projects involving painting, scent, and textile-based installation. Morris writes prolifically about art, perfume, and culture, contributing to such publications as Artforum.com, Viscose Journal, Flash Art, Femme Art Review, and Fragrantica.com. Morris serves as adjunct faculty in the Painting and Drawing Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

@heartmattmorris / website